Why This Matters for Psychology

If you’ve taken a statistics course, you’ve probably spent most of your time learning about p-values, null hypothesis significance testing, and whether your results are “statistically significant” at p < .05. This approach—called frequentist statistics—has dominated psychology for decades. But there’s another way of thinking about probability and evidence that’s becoming increasingly popular in psychological research: Bayesian statistics.

The beauty of Bayesian thinking is that it actually matches how we naturally reason about the world. When you encounter new evidence, you don’t wipe your brain clean and start from scratch—you update what you already believe. Bayesian statistics formalizes this intuitive process in a mathematically rigorous way.

The Core Insight: Updating Beliefs with Evidence

Imagine you’re a clinical psychologist, and a new patient walks into your office complaining of persistent sadness and loss of interest in activities. Before they say another word, you already have some sense of how common depression is in the general population—let’s say around 7% of adults experience major depression in a given year. This is your prior probability or just your “prior”—what you believe before seeing specific evidence about this particular person.

Now your patient mentions they’ve been experiencing these symptoms for three months, along with sleep disturbances and difficulty concentrating. This new information is your evidence or data. The question Bayes’ Theorem helps you answer is: Given this evidence, how should you update your initial estimate of the probability that this person has depression?

Bayesian statistics gives you a principled way to combine what you knew before (the base rate of depression) with what you’ve just learned (the symptoms) to arrive at an updated belief—called the posterior probability.

Bayes’ Theorem: The Simple Version

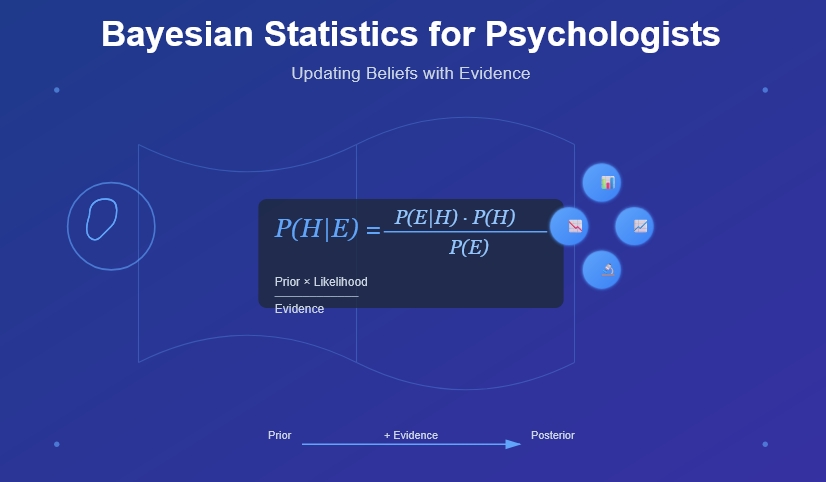

At its heart, Bayes’ Theorem can be expressed in words like this:

Your updated belief = (Your prior belief × How well the evidence fits your hypothesis) / How likely the evidence is overall

Or more technically:

P(Hypothesis | Evidence) = P(Evidence | Hypothesis) × P(Hypothesis) / P(Evidence)

Let’s break down what each piece means:

- P(Hypothesis | Evidence): The probability your hypothesis is true, given the evidence you’ve observed. This is called the “posterior” and it’s what you’re trying to find out.

- P(Evidence | Hypothesis): The probability you’d observe this evidence if your hypothesis were true. This is called the “likelihood.”

- P(Hypothesis): Your initial belief about the hypothesis before seeing the evidence. This is the “prior.”

- P(Evidence): How probable the evidence is under all possible hypotheses. This serves as a normalizing constant.

A Concrete Psychology Example

Let’s say you’re studying memory, and you want to know whether a particular study technique (spaced repetition) improves recall compared to massed practice (cramming).

Your Prior: Based on previous research and theoretical understanding, you believe there’s a 70% chance that spaced repetition is better than cramming.

Your Experiment: You run a study with 30 participants. Those who used spaced repetition remembered an average of 18 out of 20 words, while those who crammed remembered 12 out of 20.

The Bayesian Approach: Instead of asking “Is this difference statistically significant?” (the frequentist question), you ask “Given this data, what’s the probability that spaced repetition is actually better?”

Bayesian analysis lets you combine your prior belief (70%) with your experimental evidence to get a posterior probability—maybe it updates to 95% after seeing the strong results. If your results had been weaker or more ambiguous, your posterior might have stayed closer to your prior.

Why This Matters: Key Advantages for Psychologists

1. You Can Incorporate Prior Knowledge

In traditional statistics, each study is treated as if it exists in a vacuum. But research doesn’t work that way! If there are already 15 studies showing that cognitive-behavioral therapy helps with anxiety, your new study shouldn’t be evaluated as if we knew nothing beforehand. Bayesian methods let you formally incorporate existing evidence.

2. You Get Probabilities You Actually Care About

Traditional p-values tell you: “If the null hypothesis were true, how surprising would this data be?” But what you really want to know is: “Given this data, what’s the probability my hypothesis is true?” Bayesian methods give you exactly that.

3. No More “Significant” vs. “Not Significant” Cliff

The arbitrary p < .05 threshold has caused endless problems in psychology. A p-value of .049 is “significant” but .051 isn’t? Bayesian analysis gives you a continuous degree of belief, which better reflects the gradual nature of evidence accumulation.

4. Small Samples Are Okay (Sometimes)

With traditional methods, small samples often fail to reach significance even when there’s a real effect. Bayesian methods can still provide useful information from small samples by showing how the evidence shifts your beliefs, even if it doesn’t shift them dramatically.

A More Detailed Example: Diagnosing ADHD

Let’s work through a diagnostic scenario step by step.

The Situation: A teacher refers an 8-year-old student to you because of attention problems in class.

Step 1: Your Prior About 5% of children have ADHD. So before knowing anything specific about this child, P(ADHD) = 0.05.

Step 2: Gathering Evidence You administer a standardized attention test. Research shows:

- If a child has ADHD, they score in the “impaired” range 85% of the time

- If a child doesn’t have ADHD, they score in the “impaired” range 10% of the time

This child scores in the impaired range.

Step 3: Applying Bayes’ Theorem

We want to know: P(ADHD | Impaired Test)

Using Bayes’ Theorem: P(ADHD | Impaired) = P(Impaired | ADHD) × P(ADHD) / P(Impaired)

We know:

- P(Impaired | ADHD) = 0.85

- P(ADHD) = 0.05

- P(Impaired) = ?

To find P(Impaired), we need to consider both ways you can get an impaired score:

- Have ADHD and score impaired: 0.05 × 0.85 = 0.0425

- Don’t have ADHD and score impaired: 0.95 × 0.10 = 0.095

- Total: 0.0425 + 0.095 = 0.1375

Now we can calculate: P(ADHD | Impaired) = (0.85 × 0.05) / 0.1375 = 0.31

So despite the impaired test score, there’s only about a 31% chance this child has ADHD! This might seem counterintuitive, but it makes sense when you consider that ADHD is relatively rare, and the test isn’t perfect—many children without ADHD also score in the impaired range.

This illustrates the importance of base rates, a concept psychologists sometimes neglect.

Moving Beyond Single Updates: Sequential Learning

The real power of Bayesian thinking emerges when you update your beliefs multiple times as evidence accumulates. Your posterior from one analysis becomes the prior for the next.

Continuing our ADHD example: After the test score, you now believe there’s a 31% chance of ADHD. This becomes your new prior. Next, you interview the parents and learn the child had normal attention span until about six months ago, when a major family disruption occurred. This evidence is less consistent with ADHD (which is typically present from early childhood) and more consistent with a situational attention problem.

You’d update again, and your posterior probability for ADHD might drop to 15%. If you then observed the child in a one-on-one setting where they showed normal attention, you’d update again, perhaps dropping to 8%.

This sequential updating mirrors the actual diagnostic process psychologists use—each piece of evidence refines your understanding.

Common Misconceptions and Concerns

“Isn’t the prior just subjective?”

Yes and no. While priors incorporate judgment, they can be based on:

- Previous research findings

- Meta-analyses

- Theoretical predictions

- Expert consensus

And here’s the key: with enough data, the influence of the prior diminishes. Strong evidence overwhelms weak priors. You can also test how sensitive your conclusions are to different priors—if your conclusions hold across a range of reasonable priors, you can be more confident.

“This seems more complicated than p-values”

Initially, yes. But conceptually, Bayesian thinking is often more intuitive. The math can get complex, but modern software (like JASP, or R packages like brms) handles the heavy lifting.

“Will reviewers accept Bayesian analyses?”

Increasingly, yes. Major psychology journals now regularly publish Bayesian analyses, and some methodologists argue they should be preferred, especially for replication studies and meta-analysis.

Practical Applications in Psychology Research

Replication Studies

When you replicate a previous finding, Bayesian analysis lets you quantify evidence for both the presence and absence of an effect, rather than just failing to reject the null hypothesis.

Clinical Trials

Bayesian methods can ethically stop trials early if evidence becomes overwhelming, or continue them adaptively if results are promising but uncertain.

Individual Differences

Bayesian hierarchical models excel at estimating individual-level parameters while borrowing strength from group-level patterns—perfect for studying how interventions work differently for different people.

Getting Started

You don’t need to abandon everything you know about statistics. Think of Bayesian methods as an additional tool in your toolkit. Start small:

- Try reanalyzing some of your existing data with Bayesian methods to see how the interpretations differ

- Use user-friendly software like JASP that provides both frequentist and Bayesian analyses side-by-side

- When reading papers, pay attention to Bayesian analyses and how researchers interpret them

- Think Bayesian in everyday reasoning—notice how you naturally update beliefs with evidence

The Bottom Line

Bayesian statistics formalizes something psychologists do intuitively: update beliefs based on evidence. It provides a coherent framework for incorporating prior knowledge, quantifying uncertainty, and making probabilistic statements about hypotheses—all things that align naturally with psychological research questions.

Is it a silver bullet that solves all statistical problems in psychology? No. But it’s a powerful approach that often provides clearer, more direct answers to the questions we actually care about. And in a field grappling with replication issues and questionable research practices, tools that promote transparency and thoughtful reasoning about evidence are more valuable than ever.